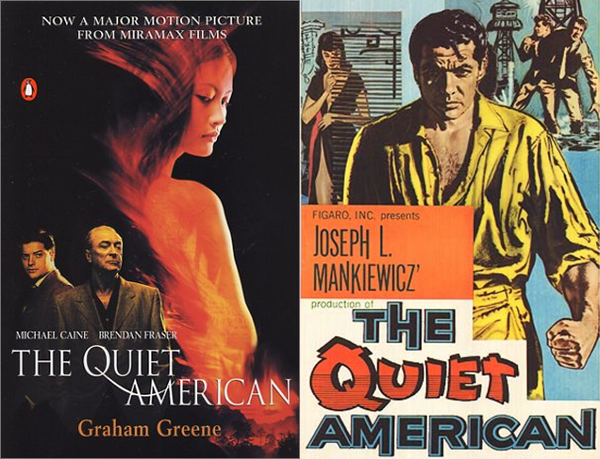

Graham Greene wrote The Quiet American in the early 1950’s while working in Saigon as a foreign correspondent. The book is an exploration of the competing moral visions of two friends, Fowler and Pyle, set against a backdrop of war, espionage, and their love for the same 20-year-old Vietnamese woman. It has been described as prophetic in its depiction of misplaced American ideals leading to misguided foreign interventionism. Whatever one thinks of this view, it is true that considerations for the sensitivities of American audiences have led to movie productions with substantial thematic changes (1958) and a delayed release around the time of the Iraq War (2002).

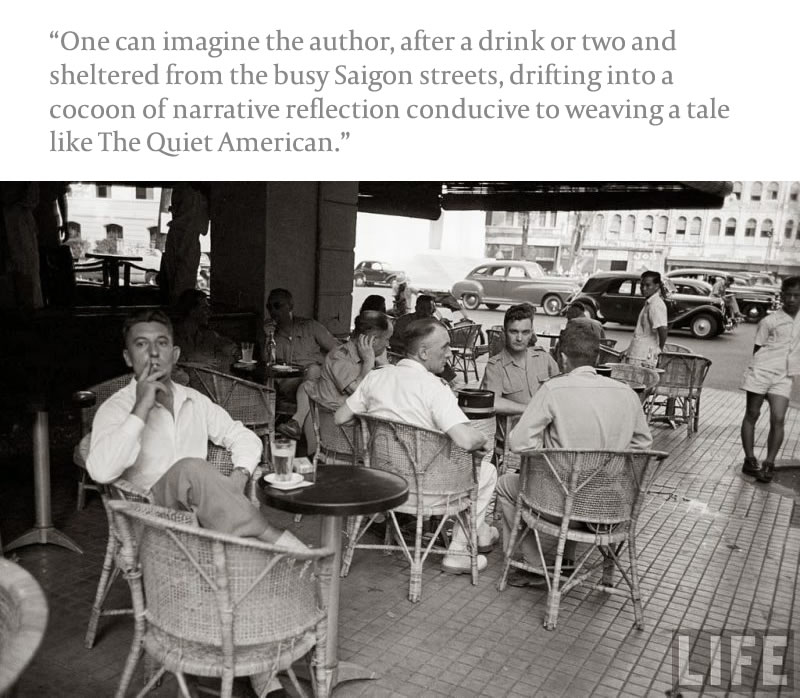

For part of his stay in the city, Greene resided at the high-end Hotel Majestic located by the Saigon River at the foot of Dong Khoi Street, at that time called the rue Catinat. It was built in 1925 in a mix of French Colonial and French Riviera styles. The luxurious lobby flaunts decorative stained glass, white columns, chandeliers, plush rugs and a pianist. Greene might have relaxed by the courtyard pool on the first floor where today tourists laze under the shade of patio umbrellas amidst rows of red and white lilies. One can imagine the author, after a drink or two and sheltered from the busy Saigon streets, drifting into a cocoon of narrative reflection conducive to weaving a tale like The Quiet American.

A love triangle: Fowler, Phuong and Pyle

Fowler is a polite but cynical middle-aged British journalist who attempts with limited success to restrict the depth of his engagement with the world. He maintains minimal focus on the well-being of those around him; for example, his primary concern is that his 20-year-old Vietnamese lover, Phuong, be available in bed and keep his opium pipe full. But at the same time, he has a nagging moral sense that finds the foreign occupation of Vietnam and the pointless violence of war repulsive.

Pyle is an optimistic young American working with the Economic Aid Mission who is sincere in his feelings for Phuong and in his dealings with others in his social circle. His concern for the welfare of those he is close to contrasts with his aseptic approach to war, which involves support for a thuggish “third force.”

And Phuong herself is a practical young woman who is looking to make a good match. Though some criticize Greene for giving her character little voice in the novel, it may not be surprising that a 20-year-old woman of her time would have more interest in quietly evaluating two rival marriage prospects than in the male-dominated world of war and politics that permeates the story. Indeed, Phuong’s reticence might be better understood as reflecting how a small country, being taken advantage of by larger powers, must make pragmatic choices while keeping its mouth shut.

Violence of 1950s Saigon

The book begins with the news of Pyle’s death, and the mystery of his murder permeates the book from beginning to end. One can still visit many of the places that Fowler did on the day of his friend’s demise, most of which are on or close to Dong Khoi Street.

Around 11:30 in the morning, Fowler goes for an iced-beer at the French colonial Hotel Continental, at 132-134 Dong Khoi Street. The upscale hotel was built in 1880 to cater to visiting Europeans, and Greene himself lived in room 214 during part of his stay in Saigon. The Saigon Opera House (1897) across the street was used at the time for meetings of the South Vietnamese Congress, and the hotel café became a popular meeting point where spies and politicians schemed and journalists sought information. Today there are still tables both outside and inside where one can sit with a drink and watch the world go by.

The Continental Hotel Saigon

The Saigon Opera House

Fowler is in the indoor part of the café when a violent explosion takes place outside. He is horrified by the scene, and after an encounter with Pyle, walks up the rue Catinat to Paris Commune Square. The Notre Dame Cathedral, constructed between 1863 and 1880, is at the far end of the square. Fowler describes it as a “hideous pink Cathedral” where “people were flocking in to pray for the dead.” Much later that day, he is summoned to 162 Dong Khoi, then the French police station, or Sureté, just off the square, where he is asked some questions about Pyle’s murder. Prisoners were known to be tortured there and Fowler describes the building as having “dreary walls” that “seemed to smell of urine and injustice.” The building is now the Ho Chi Minh City Department and Culture of Sports, and the surrounding wall is covered in propaganda posters. Also mentioned in the book is the old post office, which sits between the Sureté and the Cathedral. It is a beautiful old building (1886-1891) with Gothic, Renaissance and French influences, and is well worth a look inside.

Notre Dame of Saigon

Old post office

Post office interior

Saigon then and now

Back down at the other end of Dong Khoi Street, Fowler also paid a visit to the Majestic Hotel that night. Today, from the 8th floor open-air restaurant, Fowler might be surprised to see, on the other side of the Saigon River, eight huge Heineken billboards glowing green in the evenings, and directly in the middle of them a church quite conspicuously lit in pinkish-red, white and blue.

Fowler also makes some trips off the rue Catinat. He leaves a note for Pyle at the “American Legation”—upgraded to the American Embassy in June of 1952. The building is just a few blocks from the Hotel Majestic. Walk south along the Saigon River and take a right at Hàm Nghi Street and you will find the building on the first corner on the left at 39 Hàm Nghi Street. It now serves as a Banking University. Note that this building is not the location where pictures were taken of helicopters evacuating Americans at the end of the Vietnam War, which occurred from a reinforced rooftop shack at the CIA Office. (That building is visible from Fowler’s route along Dong Khoi Street if one stands facing the modern Vincom Center at 100 Dong Khoi Street, and looks left upwards towards the top of the adjacent block where the building that housed the Sureté is. I’m told tours of the structure are possible if you ask the security guard across the street.)

American Legation

After visiting the Hotel Majestic, Fowler dines at a fictional restaurant called the Vieux Moulin near the Dakow bridge, under which Pyle’s body is found laying in the mud. The bridge is just a few blocks south of the Hotel Majestic. The area looks much different now than it did when it was lined with shanties. The Dakow bridge has been rebuilt in recent years, and a park runs alongside the estuary where retaining walls have been installed.

Fowler also makes a trip west by bicycle to Cholon, Saigon’s Chinatown, to visit Mr Chou’s godown—or warehouse—at the Quai Mytho on the Saigon River. The Chinese community here dates back to the late 19th century, and today there are many Chinese restaurants and examples of classical Chinese architecture.

Pyle lived in one of the rooms of the Grand Hotel overlooking the Dong Khoi Street. The hotel, at that time known as the Saigon Palace, rented out apartments. An old photo shows it pretty rundown around that time, but today the exterior has been given a good facelift with a spotless off-white stucco exterior. Uniformed staff open the door to a lobby with an antique trishaw on display just in front of an old elevator that has been in operation since the 1930’s. There is an upscale “coffee lounge” off to one side, and on the top floor of a recent addition to the building, there is a rooftop restaurant where one can get excellent views of the city in several different directions.

Grand Hotel Saigon

Regrettably, some buildings mentioned in the book have been demolished, such as the art-deco-style building where Fowler considered moving after Phuong left him for Pyle, at 213 Dong Khoi Street, and the “milk bar” across from the Hotel Continental where Phuong used to visit called the Givral Café, as well as the Saigon Tax Trade Centre at 135 Nguyen Hue. But strolling down Dong Khoi Street, one can almost see Fowler and Pyle sitting at the Hotel Continental cafe chatting amiably over a beer, with Phuong sitting between them looking on in measured silence.

James Weitz—June 2018

Jim Weitz is author of the novel Gonzo Global Inc., a satire of globalization in which Mexican tap water is exported to the United States and sold as a laxative. He has lived in Asia and Latin America for most of the last 15 years. During that time, he has worked as a technical editor and taught at universities in Latin America, China and Taiwan. Previously, he worked on anti-corruption issues at the Organization of American States, and earlier at the World Bank. His stories have appeared in the journals Red Savina Review and Pennyshorts. Weitz has an MA in Applied Linguistics with a focus on cross-cultural communication from Nottingham University, and a Juris Doctor from the University of Minnesota. He is also a fiction editor at www.ojalart.com.

Images of Saigon by James Weitz