Nutmeg farms are stunningly beautiful. The smell of cinnamon, cloves, pepper and nutmeg fill the air.

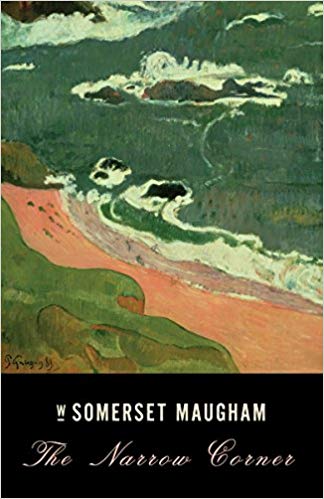

In Somerset Maugham’s 1932 novel, The Narrow Corner, three worldly travelers, all practical-minded criminals of a sort, dock at the remote Dutch colonial island of Banda Neira, called Kanda Meira in the book, during a journey through the Spice Islands of the Banda Sea. They encounter two naïve tropical island dropouts from Europe, Erik and Firth, who seem to be living in dream-worlds of their own making. A collision of world-views occurs, leading one of the characters to his death.

In Somerset Maugham’s 1932 novel, The Narrow Corner, three worldly travelers, all practical-minded criminals of a sort, dock at the remote Dutch colonial island of Banda Neira, called Kanda Meira in the book, during a journey through the Spice Islands of the Banda Sea. They encounter two naïve tropical island dropouts from Europe, Erik and Firth, who seem to be living in dream-worlds of their own making. A collision of world-views occurs, leading one of the characters to his death.

The story’s clash between idealism and practicality is, even today, reflected in Banda Neira’s idyllic setting and fascinating history. The idealism: Here and in other nearby Banda Islands, crystal clear waters, coral reefs and colorful fish make for amazing diving. Beautiful old Dutch colonial houses with wide front porches dot the island. Nutmeg farms are stunningly beautiful. The smell of cinnamon, cloves, pepper and nutmeg fill the air. There are no McDonalds, no Starbucks or other fast food chains. Credit cards are accepted by only one business. The island itself is of such insignificant size, that Apple Maps does not even credit the land-mass with a name.

The local Banda dialect (different from the original Banda language) is a beautiful lilting language, so similar in its intonation to Italian, and to some extent in its pronunciation, that it sounds like, well … Italian. “We hear that all the time,” one Bandanese told me. Speakers seem to use gentle accentuation to soften disagreements or complaints or sometimes to emphasize a point. Below are audio samples of Bandanese making daily conversation on a small boat and playing music and singing by the sea.